Imagine after 10 months you would just stop getting paid for the rest of the year. But you cannot just go on a vacation or a holiday, you still have to work until Christmas or New Year’s Eve by the side of your colleagues, doing the same job – maybe better, maybe worse than some of your colleagues, but still the same amount of work. Feeling unequally treated?

This year the European Equal Pay Day was on November 4. Each year this date marks symbolically the day women get stopped being paid for their work, compared to their male colleagues. In 2017, the gender pay gap in the EU was on average 16 percent, based on gross hourly earnings. That means for every Euro a man earns, a woman earns 84 Cents.

“When you go to the store, you don’t get a woman’s discount, you have to pay the same as everybody else,” says Hillary Clinton in an interview for a documentary on the gender pay gap. Also in the US, a woman earns around 80 cents on the Dollar, slightly less than women in the European context.

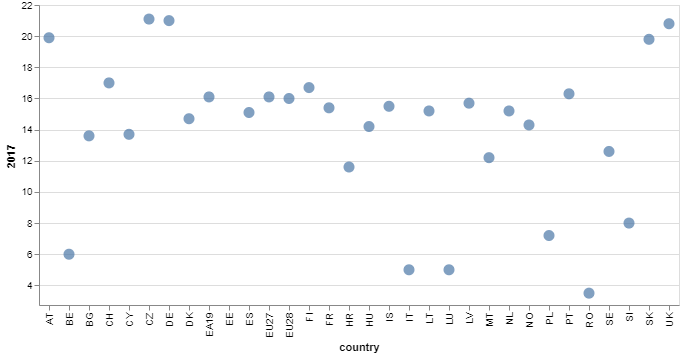

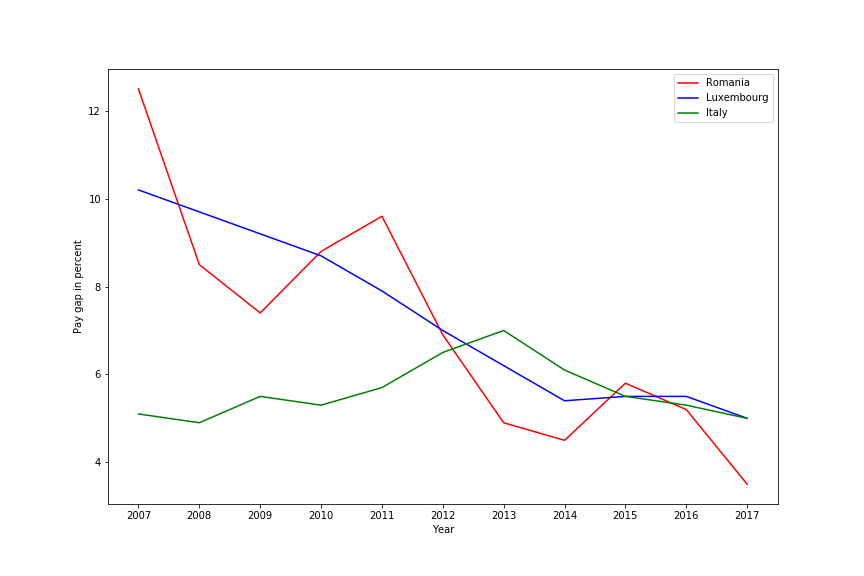

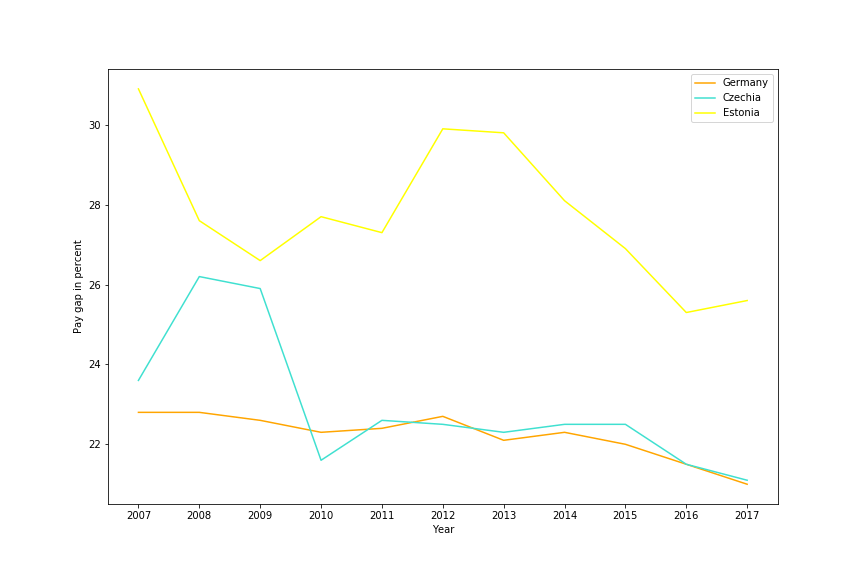

However, the EU has big differences within itself. According to numbers by Eurostat, the countries doing best are Romania (3.5 %), Luxembourg (5 %), and Italy (5 %). The countries doing worst are Czechia (21 %), Germany (21.1 %), and Estonia (25.6 %). Surprised? Often, Scandinavian countries are found at the top of these kind of rankings. In fact, Sweden is ranked 9th, Denmark on rank 13, and Finland on 20 out of 26 EU countries on the list.*

Gender pay gap of 2017 in percent

Development of the countries doing best and worst

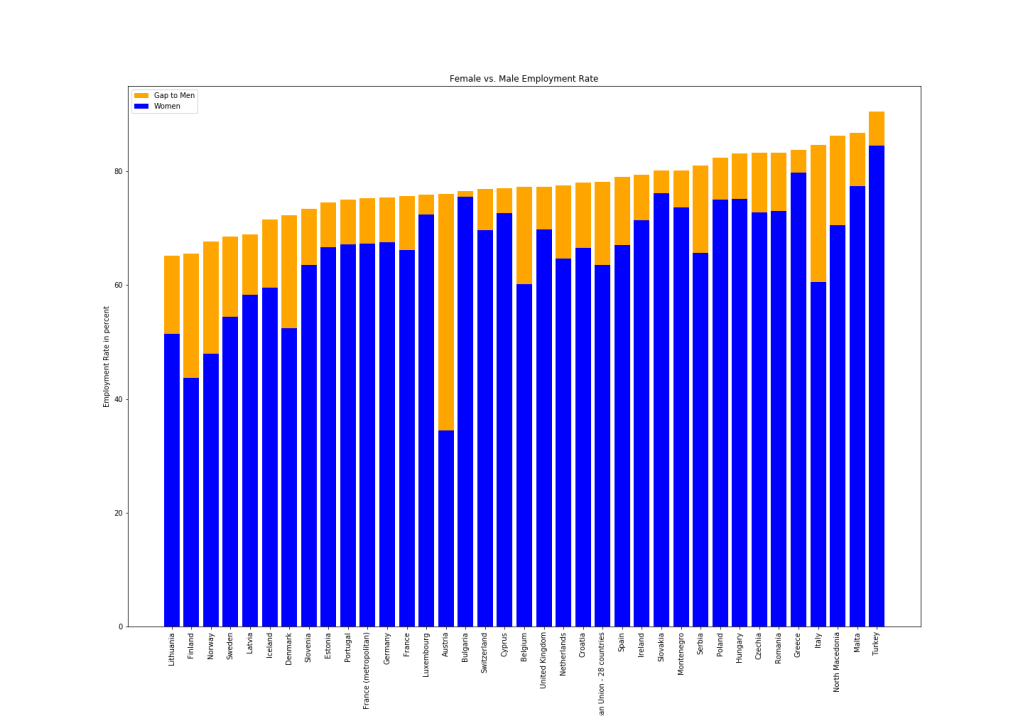

Italy’s small pay gap can be explained by its low female employment rate. A smaller gender pay gap does not mean everyone earns the same. Generally, women are more likely to stay at home and that means the more stay-at-home women a country has, the less women there are to compare. And if a woman does work against the cultural norm, she might have a higher job, or more likely to have a career while mainly men work cover lower paid jobs.

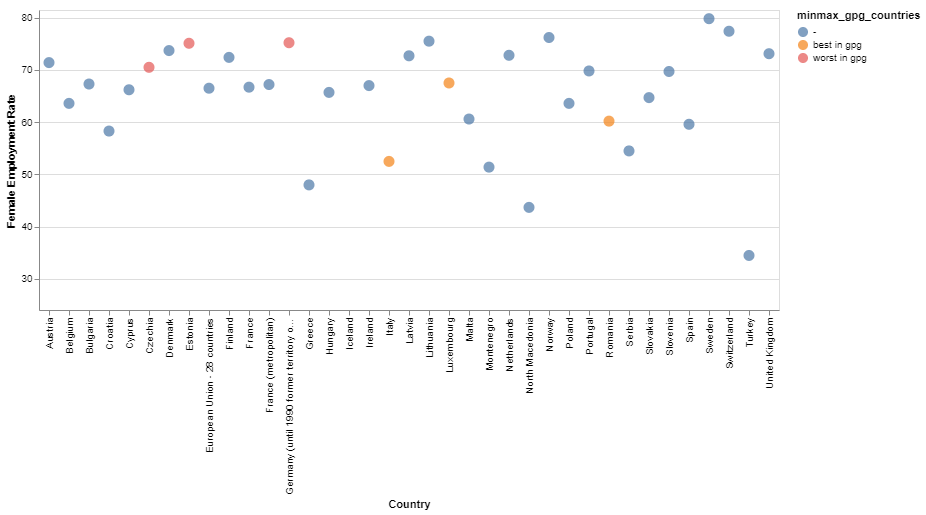

Contrary, a high pay gap can often be seen in countries where either women or men are pre-dominant in a certain sector or kind of job, like in Czechia, Estonia and Finland. Child care, social services workers are educators are predominantly female professions while personal finance advisors, web developers or engineers are mostly men. A higher pay gap can also be based on many women working part-time, like in Germany or Austria. In fact, numbers show that the three countries doing best in the gender pay gap (Italy, Romania, and Luxembourg – orange in the scatterplot) all have significantly lower female employment rates than the three countries doing worst in the gender pay gap (Czechia, Germany and Estonia – red in the scatterplot).

Female employment rate in percent

Less spread than the term pay gap is the term gender employment gap that describes the gap between the percent of employed men versus the rate of employed women. Neither of them is enough of an indicator for gender equality alone as the reality behind it is more complex than just looking at employment or earnings isolated. Studies have shown that the gap is not mostly between women and men, but women with family and everybody else. When a man and a woman start the same career path, they actually have a somewhat equal starting point, studies show the gap starts increasing as soon as a woman had her first child.

If a couple works the same number of hours in their jobs, a woman works on average nine more hours per week on household and child care. Women are more likely to stay at home when the child is sick or has an appointment. Hence, men are more likely to be promoted as mothers seem less flexible and the fathers are perceived more dedicated to their work.

Estonia, being mentioned as the country doing worst on the gender pay gap (25.6 %), was for a long time one of the countries with the most generous maternity leave rates. Maternity leave is a great policy, but it can reinforce cultural norms: mothers stay at home, fathers work, get promoted and women have fewer chances. That is why it is important to give parental leave to both, fathers and mothers. And that is where Scandinavian countries are ahead, compared to the rest of the world. According to a ranking by Insider, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Sweden, and Denmark are the top five countries to be a mother in based on maternity leave, maternal health, children’s well-being, the country’s economy and education, and the participation of women in the government.

For example, Iceland (not part of the EU) has with 84.5 % the highest female employment rate in the world. One of the reasons is that they changed the maternity leave they already established in the 80s to a paternity and maternity leave in 2000. If fathers do not take this time, they lose it and are in that way gently ‘forced’ to take it, which creates more equality in the labor market.

There are many factors that need to be taken in consideration when looking at gender equality and working on closing the gender pay gap is certainly an important step. However, it is just one of many factors in a bigger context, next to employment rate of women, parental leave and others. The most effective way to work on the gender pay gap starts with fathers: offering them parental leave, from the policy side, or the possibility to work part-time, from the business side. After all, that would provide more equality, and then women can still decide to be housewives or working part-time if they want, but they can also decide not to if they do not.

(* Ireland and Greece did not have available numbers in the most recent data from 2017).